Leafing Through History

Since early 2021, an intercollege, interdisciplinary team of NC State researchers has been using modern scientific techniques to mine genetic clues from old manuscripts. In doing so, they are uncovering traces of the past hidden in the books and shaping future scholarship.

The team, supported by $25,000 in Research and Innovation Seed Funding (RISF) from the university, has analyzed DNA from 91 parchment manuscripts in a collaborative project that links the humanities and the sciences. The researchers said the biological data collected reveals the species of the animal skins used to make the parchment and offers insights into aspects of medieval life — from animal husbandry, agricultural history and economics to book production and more.

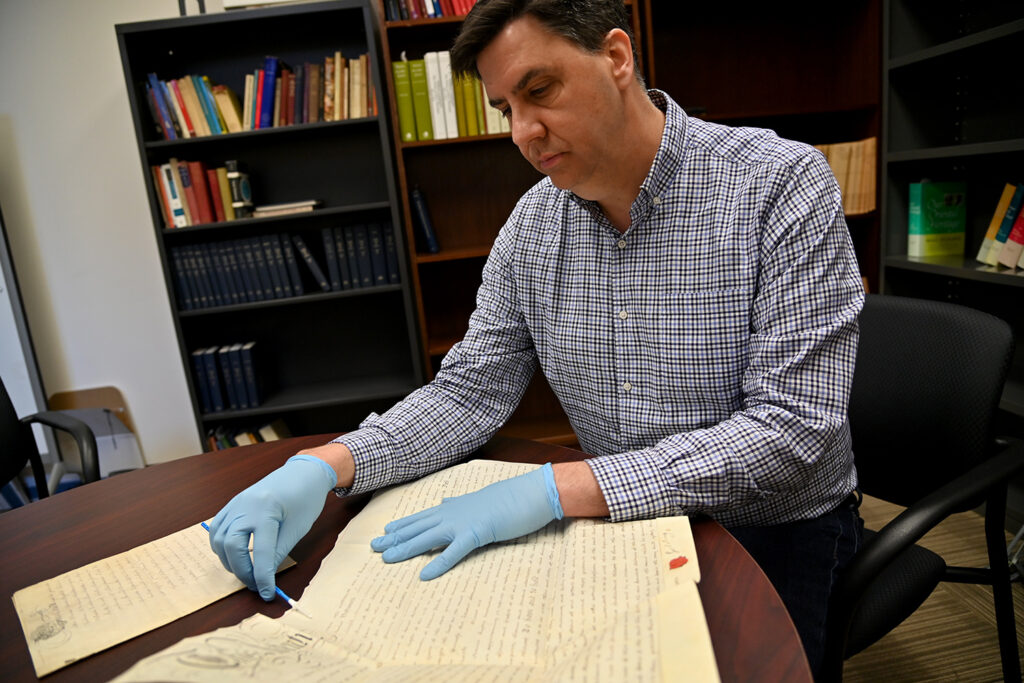

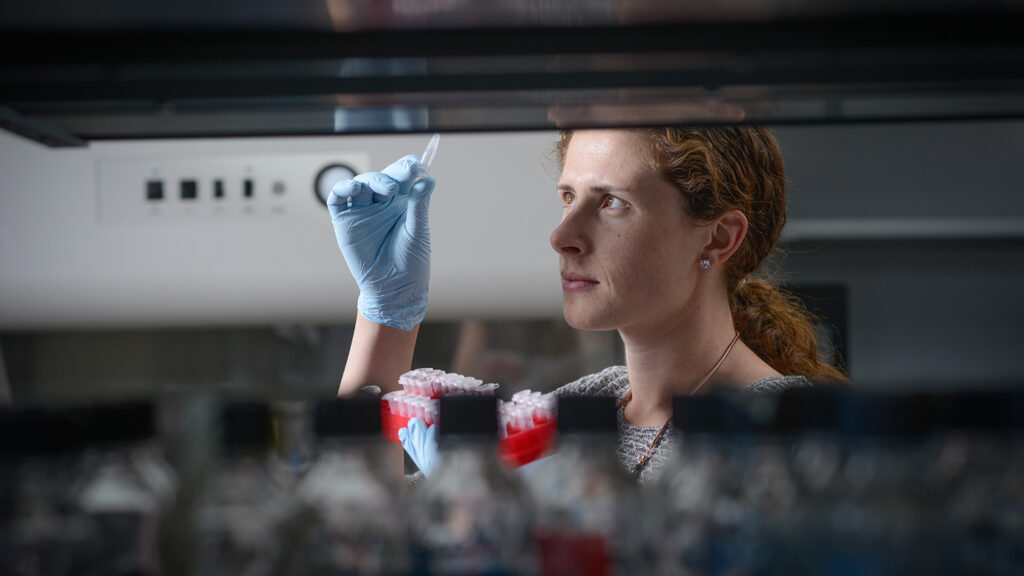

The co-principal investigators of the project, which concludes in June, are Tim Stinson, associate professor of English in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, and Kelly Meiklejohn, assistant professor of forensic science in the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Joining them as co-investigators are two other CVM faculty: Matthew Breen, professor of genomics and the Oscar J. Fletcher Distinguished Professor of Comparative Oncology Genetics, and Benjamin J. Callahan, associate professor of microbiomes and complex microbial communities.

Previously, scholars were interested in manuscript books for the texts and art they contained, and paid little attention to parchment, the primary material used in these books. But studying the parchment in the manuscripts, which date from 700 to 1700 AD, through the lens of science offers a way to reconstruct a fuller, more complete historical picture by filling in gaps in the written record.

Even more, the tests are being done without destroying the parchment, which the researchers describe as an untapped archaeological resource.

“This is radically interdisciplinary,” Stinson says. “It brings together different ways of understanding the world, and there’s no way we could address these problems without both sides.”

Meiklejohn agrees.

“When we have group meetings and discussions, we’ll often say, ‘Oh, that’s an interesting idea.’ How could we, as scientists or data analysts, help answer that question? What tools would we need to harness?” She says. “And I think that’s how we come up with new ideas and move our work forward.”

From the data collected, the researchers identified that goats, cows or sheep were the most common species used to produce the parchment. They also detected regional differences, with goats more commonly used in manuscripts produced in Ethiopia while sheep were more commonly used in books made in Europe.

“Between the early to late Middle Ages not much is known about parchment as a commodity and animal husbandry, or when book production specifically shifted to trade guilds from particular monasteries,” Stinson says “This kind of data could answer those sorts of questions and others.”

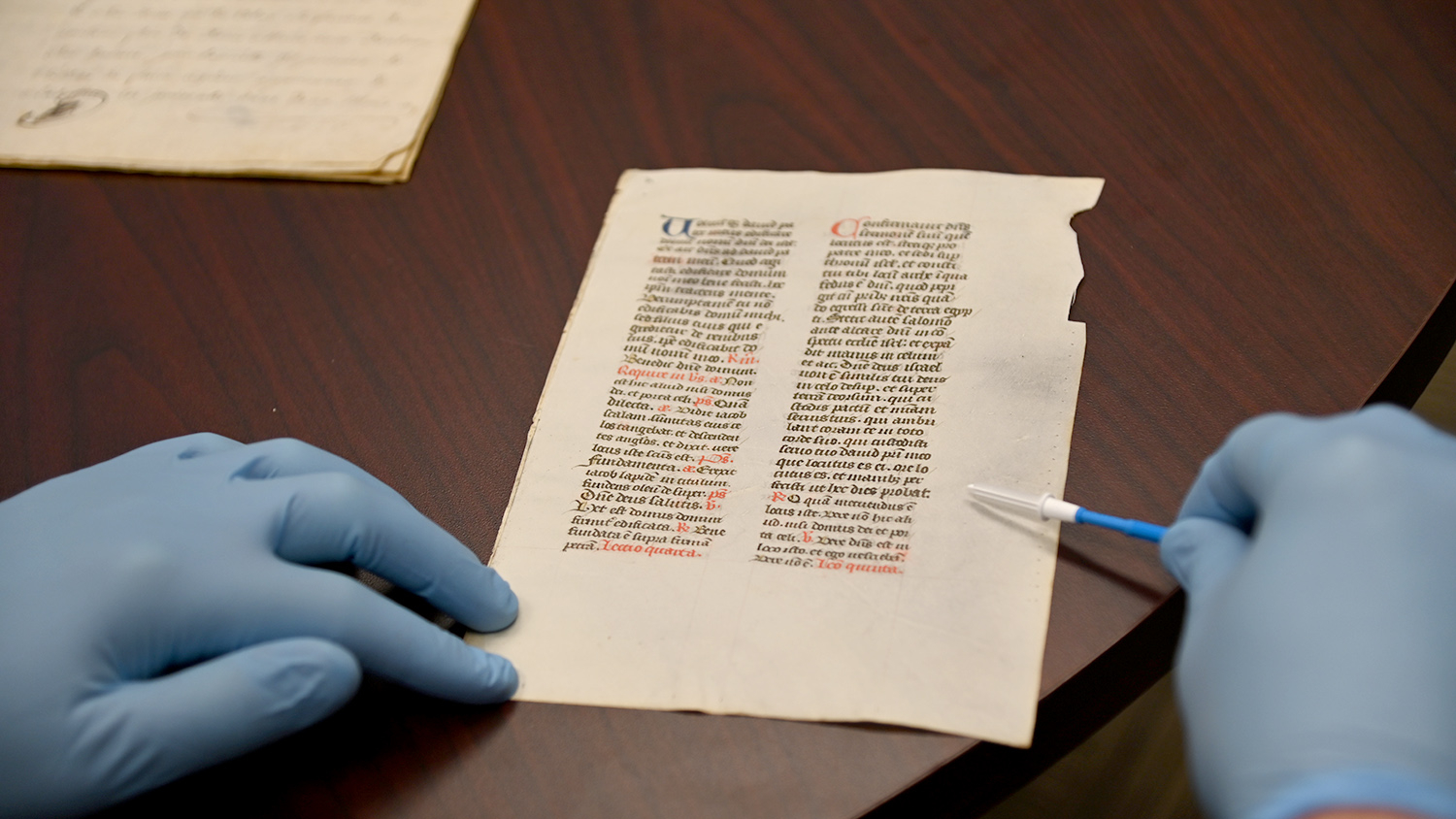

To obtain samples, the researchers rubbed some of the parchment using an eraser technique. They brushed others with cytology brushes, following a technique developed by professor Melissa Merrill’s lab in NC State’s Department of Animal Science, which proved faster and more efficient, notes Meiklejohn.

Then they incubated the DNA from these tiny samples overnight in an extraction buffer and purified and measured the genetic material in each. The isolated DNA was tested and analyzed to determine the species used to make the parchment.

As the study proceeds, the added hope is that the extracted DNA will provide a way to determine “consistently” the sex of the animal skin used to make the parchment. It could also conclude whether the sample is viable for analysis, says Callahan, a computational biologist.

The researchers said their work validates non-invasive genetic extraction techniques and can be applied to different areas of the humanities and sciences. It also offers NC State “the opportunity to shape an emerging field” known as biocodicology – the study of biological information stored in manuscripts, Stinson says.

This is not NC State researchers’ first foray into extracting DNA from parchment. Stinson published a paper on the subject in 2009 after discussing the idea with his brother, a biologist. However, once he proved extraction was possible securing funding proved difficult.

Since then, substantial advancements have been made allowing highly fragmented and low-quantity DNA to be sequenced more easily. Also, prominent bioarchaeologist Matthew Collins reached out to Stinson to collaborate on several interdisciplinary projects. Collins’s research group in England has been at the forefront of studying DNA from objects such as parchment and its members have developed some testing procedures.

Stinson, who earlier worked with professor Melissa Merrill’s lab, then sought out other collaborators on campus. In 2019, he joined his current CVM partners and pursued funding from the RISF program.

That program “looks to fund interdisciplinary multi-college work, and this is one of those projects that just fits that mold, really, really, well,” noted Breen.

The team also partnered with Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Books Library. The library’s special collections room is where the manuscripts are housed and the tests were conducted.

What’s next? The researchers said the project’s findings will enable them to seek external funding and collaborate beyond NC State’s campus with various universities, libraries, and museums, and with diverse scholars, including scientists, humanists, librarians and museum curators.

“Medieval books were interdisciplinary products of monks, scholars, parchment makers and ranchers,“ adds Stinson. “Today, it takes a similarly diverse group to understand these artifacts in their full capacity.”

This post was originally published in College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Categories: